Hiraeth

Video still. Courtesy of the artists.

archived

23 Mar

–

20 Apr

Holly Walker, Sylvan Spring

Hiraeth is a Welsh word describing a spiritual longing for a place that we have never been. It is the lost ancient places we imagine our ancestors would stomp their feet into their lands and the grief we struggle to locate in our bodies—a dislocated homesickness for a motherland we have never belonged to. The offerings of this exhibition illustrate the artists’ intimate and awkward rituals of becoming truly Pākehā—tangata Tiriti on their haerenga towards becoming familiar with the layers of their cultural identities and realities on this whenua and in relation to its people.

Hiraeth is a Welsh word describing a spiritual longing for a place that we have never been. It is the lost ancient places we imagine our ancestors would stomp their feet into their lands and the grief we struggle to locate in our bodies—a dislocated homesickness for a motherland we have never belonged to. Sylvan Spring and Holly Walker have researched and worked collaboratively to illustrate the intimate and at times awkward rituals they engage with, in a concerted effort to become truly Tangata Tiriti.

Spring and Walker’s haerenga towards reconciling the layers of their cultural identities on this whenua and in relation to its people is informed by wisdom from te ao Māori and the Māori in their lives, while acknowledging that the only way to be accountable as Pākehā is “to be clear in our identity – to embrace it, not escape it.” A common refrain in Imagining Decolonisation is that colonisation is bad for everyone and while the voices of Māori should always be placed at the centre, Pākehā also need to put in effort as “decolonisation is the work of us all.”

As stated by Amanda Thomas,

One of the really exciting aspects of decolonisation is that it can help Pākehā better understand who we are. In doing the work of decolonisation—developing a better understanding of the history of this place and creating a more equitable society rooted in Māoriness—Pākehā will find out more about our own histories, our own families and our own culture.

Spring and Walker are concerned with actively questioning their relationships with their ancestors and how this shapes their reality in Aotearoa, an issue more and more commonly raised by Pākehā artists of late. This exhibition presents the findings of their decolonial and familial embodied research in the form of documentary photographs, performance and audio works.

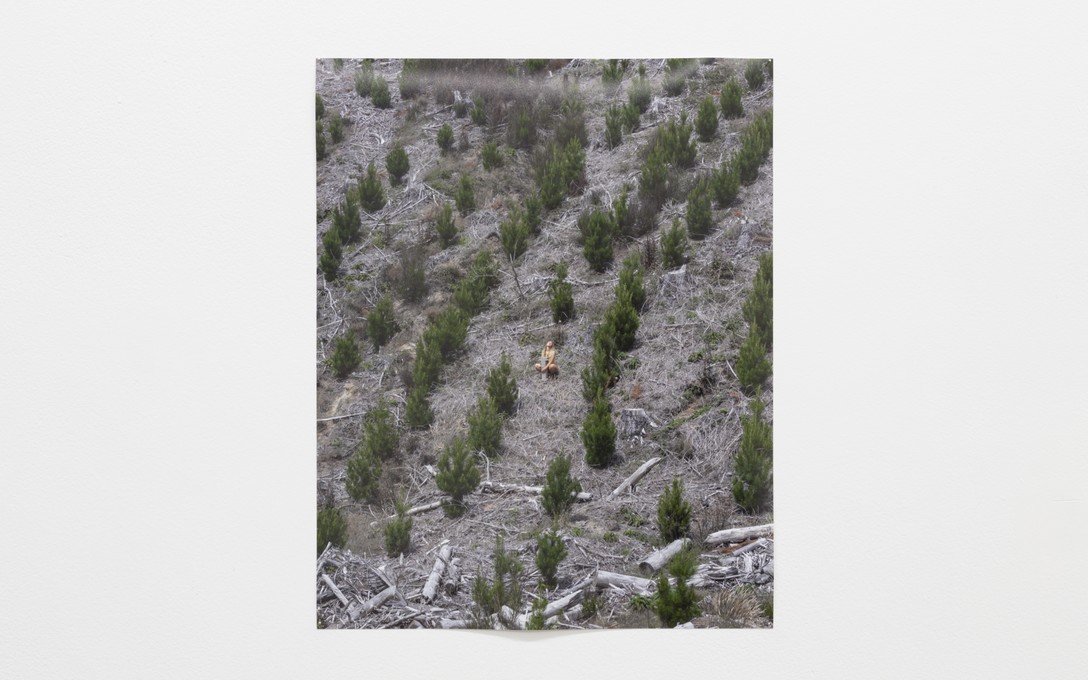

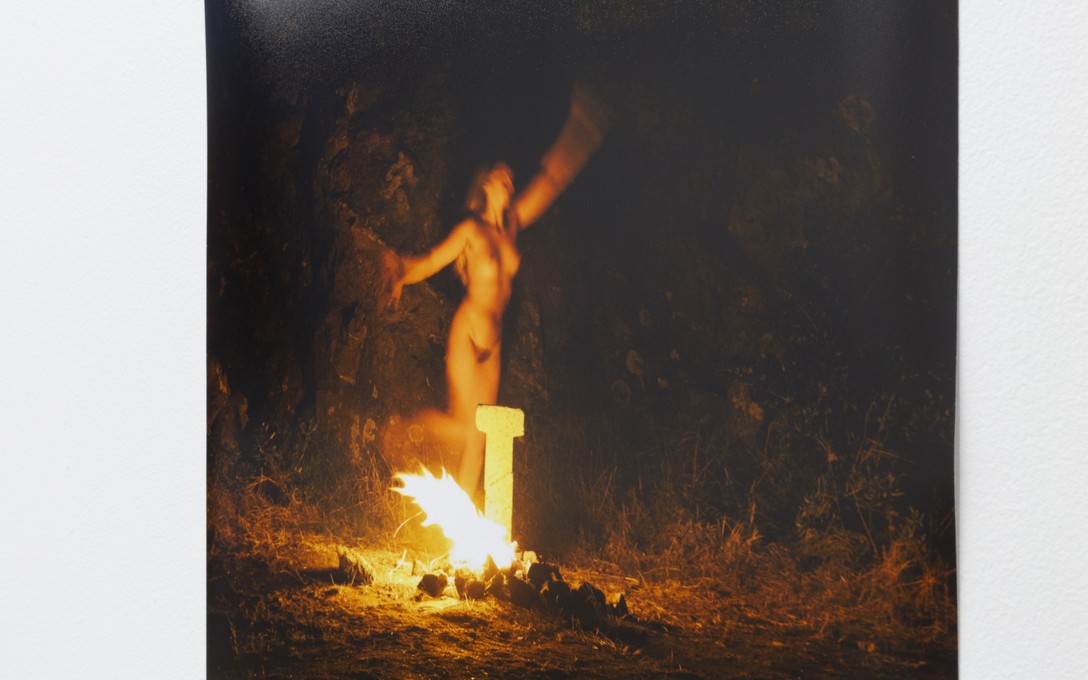

Walker has contributed a collection of photographic works which document an endurance practice of navigating landscapes in Te Ika-a-Māui with a concrete found object in the shape of an ‘I’. The work embraces the paradox of belonging to both a fragmented lineage with its own cultures that have been negatively impacted by colonisation and capitalism in their own right and a monolithic sense of settler-colonial whiteness that has brought so much harm to Indigenous peoples. Walker carries the weight of her ‘I’ with her, through deserts and construction sites—an uncomfortable assertion in the environment and against her body, while a necessary attachment and weight to bear. Though photographed alone by her partner Nayte, she understands her work to always be in relationship with Papatūānuku, therefore a Te Tiriti based practice. At times the 'I' brings moments of irony, in addition to the ritualistic representations performed by the body and the mauri of the landscapes. Far from the first artist in Aotearoa to utilise an ‘I’, Walker’s employment of this symbol on the whenua is an examination of her body in relation to it in full awareness that the people she descends from have long been separated from their own.

The artists collaborated on a moving image work ritualising the cèilidh, a Scottish and Irish dance tradition. The embodied performance of cèilidh connects them to their whakapapa and each other through movement, whilst demonstrating the foreign disconnect felt as Pākehā. Filmed by Fraser Walker at Oruaiti Breaker Bay, this work steps towards learning and reclaiming ancestral practices lost to colonial cultural amnesia. Spring and Walker begin their ritual at dawn, creating patterns and allowing the marks to be washed away by the sea back to their ancestors. The dances featured in the video are the Gay Gordons from Scotland, the Waves of Tory from Ireland (which is a celebration of the ocean), and Cylch y Cymru from Wales.

A looped audio recording of Spring singing the traditional Irish song ‘Óró, sé do bheatha ‘bhaile’ also plays in the space, accompanying the photographs and moving image while remaining a work on its own. This song was used prominently by Irish during both the Jacobite Rising of 1745 and the Easter Rising of 1916, as a protest song opposing their ongoing colonisation by the English. Neither the Third Jacobite Rising nor the Easter Rising were immediately successful, but both are part of a chain of events that led to the declaration of an independent Irish republic in 1919. The singing of this song is intended as a grounding in the colonial struggles of Spring and Walker’s ancestral homelands, to accompany the joy of dancing with the pain but also undying hope of these struggles, and as a specifically ancestral reminder of their commitment to and solidarity with decolonial action in Aotearoa and abroad.

Past Event

Artist Talk: Sylvan Spring and Holly Walker

Join curator Brooke Pou for a kōrero with Sylvan Spring and Holly Walker about their exhibition Hiraeth.

More info

Sylvan Spring and Holly Walker, Hiraeth, 2024. Image courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Sylvan Spring and Holly Walker, Hiraeth, 2024. Image courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Sylvan Spring and Holly Walker, Hiraeth, 2024. Image courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Sylvan Spring and Holly Walker, Hiraeth, 2024. Image courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Sylvan Spring and Holly Walker, Hiraeth, 2024. Image courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Sylvan Spring and Holly Walker, Hiraeth, 2024. Image courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Sylvan Spring and Holly Walker, Hiraeth, 2024. Image courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Sylvan Spring and Holly Walker, Hiraeth, 2024. Image courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Sylvan Spring and Holly Walker, Hiraeth, 2024. Image courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Sylvan Spring and Holly Walker, Hiraeth, 2024. Image courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Sylvan Spring and Holly Walker, Hiraeth, 2024. Image courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Sylvan Spring and Holly Walker, Hiraeth, 2024. Image courtesy of Cheska Brown.

Sylvan Spring

Sylvan Spring is a Pākehā (Eire, Alba, England, Deutschland) writer and occasional music maker who has been shaped by the lands and waters of Te Whanganui-a-Tara and Te Awakairangi. Their first book of poetry Killer Rack was released this February through Te Herenga Waka University Press.

Holly Walker

I tipu ake au i Te Puke. Kei te noho au ki Pōneke ināinei. He Pākehā ahau, he Tangata Tiriti ahau, ko Holly tōku ingoa. Holly Walker is a multimedia artist, recently practicing in performance, photography, sculpture, video and written works. Holly’s work subjects her body as a performative foundation to explore and represent politics of identity.

Special thank you to Nayte, Fraser Walker, Tuuii, Pounamu Rurawhe, Steve Walker, Derek Cowie, and Becky Bean.